A growing number of us, meaning us humans, will be pretty much stuck in their homes for a while. When I posted this, confirmed cases of the rather contagious and virulent Covid-19 respiratory disease has surpassed 188.000, its deaths 7.400. Policymakers and medical experts are trying hard to manage and fix this crisis. I admit I do feel a bit tense, since who knows what’ll happen. Personally, I’m trying to find some comfort in reading up on the handling of the early modern plague.

Just Disease

Only very recently have we begun to understand what diseases are and how they are caused. The ancient Greeks believed a patient was just sick, and that no further qualification applied. ‘Healthy’ was a singular box which was either checked or not. For all his mistakes, Hippocrates at least tried to teach that sickness was a natural occurence. Sadly, he could not prevent people from thinking diseases were caused by a deity, perhaps displeasured by sins, to which some in Christian societies attributed it. Sometimes they were looking for the cause in another person, allegedly possessed by the devil.

Over the centuries, people did start to move away from places where for some reason their neighbours were dropping dead en masse: a geographical element was recognised. Depending on the variant, plague killed within hours or days, after heavy fever, severe headaches, hallucinations and infected lungs or bursting swollen lymph nodes known as ‘buboes’. By early modern times, armed mostly with assumptions, thinking went in the right direction: infected humans were dangerous when close. This was certainly true for pneumonic and septicemic plague. Bubonic plague needed fleas and rodents to reach humans. Especially in terms of medical treatment, knowledge and means were still lacking.

To Withstand Turks, Plague or both?

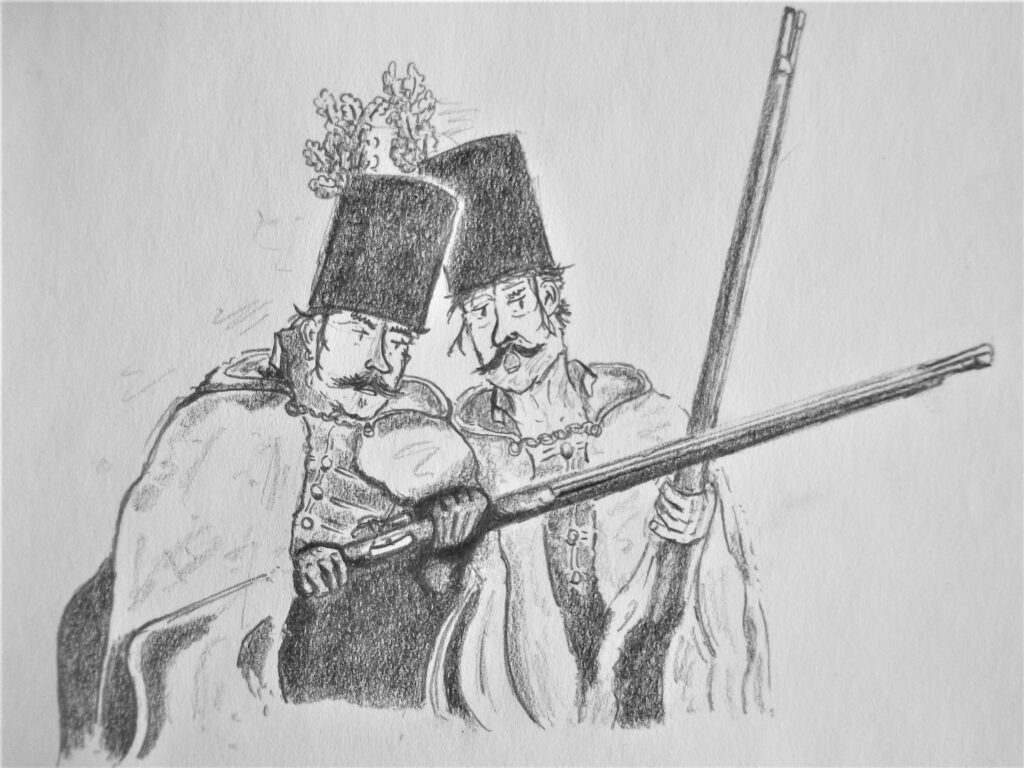

This resulted in state measures being extremely blunt when compared to today’s standards. For centuries the Habsburg Empire shared a long frontier with their Ottoman counterparts on the Balkans. The Turkish controlled lands were hotbeds of Yersinia pestis, the bacterium causing the plague. In war, soldiers brought it north and west; while at peace, traders did. Historian Boro Bronza tells us that by the 1760s, the Habsburgs had quite firmly established a defense system against the diseases. Not by medical means, but by force of arms. At all times 4.000 men guarded the border, which meant approximately two for every kilometer. Plague in Istanbul meant an increase to 7.000. If it occured in an Ottoman border region: 11.000.

When the Habsburgs were sure no outbreak had occured across the border, travellers were still kept in quarantine for 21 days. When they assumed it had, this figure rose to 42. 84 days of quarantine (!) awaited those seeking passage into the empire if its rulers were sure an epidemic was ongoing. Soldiers serving at quarantine stations had to spent 52 days in quarantine themselves. Unsurprisingly, trade had a tough time developing in these parts, and some turned to smuggling. Empress Maria Theresia had decreed that evading these rules was punishable by death.1Boro Bronza, “Austrian Measures for Prevention and Control of the Plague Epidemic Along the Border with the Ottoman Empire during the 18th Century”, History of Medicine 50:4 (2019): 180, 182-183.

The Habsburg system was based on Venetian methods, who were applying similar measures to incoming ships. Some historians believe these defense lines saved Europe from the plague. Others saw no causal relation, and saw the disease’s disappearance mainly as coinciding occurence. I suppose the capability to build defensive systems could even be a result of a receding disease, rather than the other way around. After all they used the military, an institution that had a growing presence in the region for two centuries to mainly battle Turks, not germs. One historian2Aaron Shakow is cited in Sam White’s piece discussed below even proposed that European quarantine existed as much for trade wars as the threat of disease.3See Bronza’s article; for an earlier overview also see Gunther Rothenberg, “The Austrian Sanitary Cordon and the Control of the Bubonic Plague: 1710–1871”, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 28:1 (1973): 15-23.

Part of Nature and the Soil?

Across the imperial divide the plague was experienced in a different manner. In contrast to a ‘foreign invasion’ analysis like Bronza’s, historian Alan Mikhail argued that for the Sultan’s Egyptian subjects bouts of disease were part of a natural cycle. Flooding of the Nile was followed by the plague. The rise of water levels drove flea-ridden rats to humans. Then came droughts and famine. The exact causal relations between plague and famine were unknown then, and are debated today.

Chroniclers even described epidemics in natural terms, one time referring to the great 1791 plague in Cairo as an “icy gale of death”. Their beliefs were thus what we call ‘miasmic’: a disease was seen as some sort of gas cloud looming over an area, or as substance embedded in the earth. The Egyptians did not flee their homeland, where caravans from the east brought both wealth and plague. Very, very cautiously, Mikhail noted that stern Islamic beliefs might have effectively prevented flight.4Alan Mikhail, “The Nature of Plague in Late Eighteenth-Century Egypt”, Bulletin of the History of Medicine 82:2 (2008): 249-275.

While Mikhail remained unconvinced, historian Sam White even ups the ante. He argued against the idea that the Ottoman Muslims were so pious as to only passively suffer God’s will. Mainly, as in Europe, wealthier people did flee during outbreaks. They had the means to travel and a place to go to in the first place. Additionally, White wrote:

The peasantry had to stay put during epidemics for the same reason they had to stay put the rest of the time: not because it violated divine law but because it violated imperial law.

The Sultan’s government tried to overcome imperial overstretch. Conquering new lands meant contact with new peoples and diseases, and the need to govern them. Demographic forces too were at play. If a population rose beyond its feeding capacity, the surplus labour force started wandering. Famine and the threat of shortages could thus indeed help spread disease. Especially during political upheaval, the people might move unchecked. Yet there were measures: newly examined sources show individual cities seeking to keep the sick out of their walls, including Istanbul. In 1566, the island of Chios still upheld its 25-day quarantaine for arriving vessels.5Sam White, “Rethinking Disease in Ottoman History”, International Journal of Middle East Studies 42 (2010): 549-567.

Judging the Ottomans as continuously sick and pious seems mainly the product of Western ignorance or oversimplicity. Such misplaced nationalist sentiments in academia have more extreme variants in politics, as the American president recently named Covid-19 a “foreign” virus. Some among us -and I hope the tiniest of minorities- even express racist sentiments towards Asian people in the streets because of the current pandemic. Doctors do great work, but there is a role to play for all when fighting diseases: this toxic language must be denounced for its divisiveness.

A good starting point for getting into the history of epidemics is this Yale lecture course taught by Frank Snowden.